The Hibernacle and the Knights of Pythias

This is the road to Central City, Colorado. It’s a classic Wild West gold mining town from the late 1800s that boomed briefly until the ore was exhausted. After that people moved away and the place began to contract. The mining that continues in the area is for aggregate crushed stone used in asphalt paving and concrete down in Denver. If you’ve ever passed through Denver International Airport or driven along Colorado’s interstate highways this is where much of the raw construction material came from. But let’s be clear, pulverized rocks sustain a town at one level, while a thick vein of gold provided something entirely different - if only briefly.

Once dubbed the “richest square mile on earth” Central City’s population peaked in 1900 with over 3,100 inhabitants. Today there are just 779 permanent residents. The hills are dotted with the overburden from long abandoned mines. After the gold was stripped out the town lost its economic engine. There were attempts to replace mining with tourism in the early twentieth century by building an opera house and cultivating various festivals, but the town continued to dwindle year after year. For a larger version of exactly the same dynamic see Butte, Montana and its depleted open pit copper mine. This one trick pony situation has been playing out in towns all over the country for a very long time.

I love exploring places like Central City because the early stages of the traditional development pattern are so clearly on display. People arrived in a new area and build the smallest, cheapest, simplest shelters possible - often tents. This was far more common than people today are willing to acknowledge. Tents were followed by log cabins and other basic wood structures. I spotted one little rustic cottage that was proudly named the Hibernacle by its owner. The portmanteau of hibernation and tabernacle seemed just about right.

Tiny one room affairs were gradually added on to repeatedly and the resulting lumpy properties often included rental accommodations, home based businesses, farm animals, and productive gardens. Note that there were dirt roads and virtually no public infrastructure or municipal services in those early days.

People used outhouses and managed to supply their own water as best they could at the household level. Bouts of disease of all kinds were common with little in the way of medical treatment. Firewood was the predominant fuel and the nearby forest was quickly denuded until coal began to arrive with the railroad spur. Central City was a messy, smelly, ad hoc collection of scrappy upstarts. This is how Denver began too.

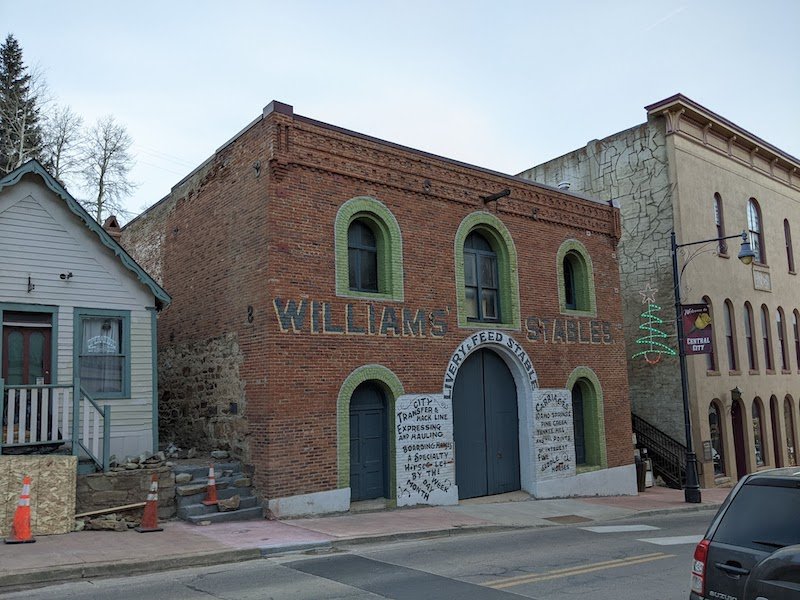

At a certain point there was enough productive economic activity in Central City that masonry buildings were constructed. Local stone was readily available on site and imported bricks began arriving by the boxcar load. A city hall, fire station, police headquarters, and other civic institutions were built as tax revenue increased. Churches of various denominations were established and eventually the more important streets were paved and fitted with public utilities. Notice how an economic base emerged first, then organized services followed - not the other way around.

The majority of the old buildings in Central City have been vacant for decades. With so few people in town there’s no way to support the businesses that once thrived there.

Peeking through the windows revealed de facto storage spaces that might once have been hotels, restaurants, general stores, and apothecaries. Some establishments look like they might have been a bank or a bordello. (Both enterprises were likely decorated in a similar fashion and patronized by the same clientele.) The goal, according to the real estate advertisements, is to cobble together enough of these small buildings to form a single large floor plate suitable for modern commerce.

In the 1990s the state of Colorado introduced legal gaming as a way to promote tourism and enhance tax revenue. Central City was one of the towns that actively cultivated gambling and associated activities. What appears from the street to be a row of small older buildings is actually a single complex. Money from gaming corporations was mingled with historic preservation funds to clean up the facades while the interiors were pieced together as the Century Casino.

The most striking thing about this place was the extraordinary degree of automation. Gone were the croupiers and dealers. Absolutely everything was based on touch screen video equipment. As far as employees, I saw a security guard, a bartender, two people behind a counter processing credit card transactions, and a janitor. I suspect there are reasonably well paid technicians who service the electronics, but I would bet good money they’re off site specialists who only visit from out of town as needed.

Most of the Century Casino complex is actually a full city block of multi story parking in rustic drag. The idea was to revive the town with a steady churn of visitors from the Denver metroplex, generate employment, and spin off municipal tax revenue. The town would be the suckerfish quietly nibbling the crumbs off the whale’s skin.

It would be tiresome to offer a critique of the Grand Z Hotel and Casino. No one expects such facilities to be timeless works of enduring beauty. They’re decorated industrial sheds that have been exquisitely engineered to welcome people in, give them an ersatz experience, strip them of their cash, and send them on their way. Fine by me. Visitors are a self selecting population who know what they’re getting into and must like that sort of thing.

The more interesting question is how successful the strategy has been for the town. Central City feels like an anemic version of Atlantic City or the new destination resort near the airport in Denver. The town is an empty vessel - a physical vector for flows of capital that arrive and depart without lingering.

I should say that walking around there’s evidence of gaming money put to good use. Retention walls, water, sewer, gas, electric, and communications infrastructure were all upgraded at some considerable expense courtesy of casino revenue. These are things that the locals (remember, all 779 of them) might not have been able to fund themselves. The cost of such public infrastructure could easily be more than the value of the modest properties they support. So you could call this a win.

But there’s another twist to this story. Right next to Central City is the town of Black Hawk which had also declined for decades and similarly decided to embrace tourism and a casino economy. However, Black Hawk is closer to the state highway than Central City and all 127 residents of Black Hawk (count them: Bob, Sue, George, Mary, Heloise, Ralph, Gloria…) decided to drop the fiction that they were an authentic pioneer town set on historic preservation and agreed to slapped up some Las Vegas style high rise hotel towers. Black Hawk has 18 casinos compared to the 6 in Central City. Mo money! It’s fair to say Black Hawk has been eating Central City’s lunch from the get go.

To combat its geographic disadvantage Central City built a private 8 mile alternative road that parallels the existing state highway by snaking around the other side of the hills. The $38M road was paid for by the Central City business improvement association. Remember, this is a town where the local residents had previously struggled to cover the costs of water and gas lines and couldn’t maintain their own retention walls. The town of Central City is now a wholly owned subsidiary of the gaming industry. That’s neither good nor bad. It just is. They traded an exhausted gold mine for some mediocre tourist traps. In the fullness of time I suspect the ending will be similar. But they bought themselves some time.

On the way out of town I stopped off at the old cemetery. These places fascinate me. There were family plots as well as separate areas for Catholics and Protestants. There might have been a spot for the Chinese who worked the railroads and mines, but I couldn’t find it. But I did stumble on a parcel dedicated to the Knights of Pythias which I had never heard of before. I did a little Googling and discovered it’s a service organization that was founded in 1864 and appears to be similar to the Elk’s Lodge and other such groups. These days they raise funds for cancer research and support food pantries for the hungry. The things you can learn by reading tombstones…

Then, just past the cemetery, was a newly minted suburban style cluster of townhouse condos. Prospector’s Run is a cookie cutter development hot glued to the side of a hill on the edge of town. Notice the current development pattern. A single master plan is executed by one company using a pool of institutional capital. All the infrastructure is built at once to a finished state. Every home is constructed to a specific standard and comes complete with a home owners association to prevent it from ever changing. There are strict limits on what can and can’t be done on the premises and who is and isn’t allowed to occupy the space and under which conditions.

I look at these homes and think about how they’ll fare over the next century or two. Will they hold up better or worse than the homes of the original settlers of Central City? Can they survive the inevitable closure of the casinos? Might they adapt over time along with the town and reinvent themselves for a new era? I won’t live long enough to know… But for now, Central City thanks you.