The Electric Shuffle

I just listened to an episode of the GardenFork podcast about electric vs. gas cookstoves. The provocative title was, “Is The Fed Coming For Your Stove?” Short answer… No. The question was raised as some local jurisdictions are promoting all electric homes as part of larger health and climate policies. As with so many things these days there’s a great deal of consternation from the Left and the Right about absolutely everything including home appliances. Are gas stoves poisoning our children and killing the planet? Will a transition to an all electric future fix everything? How exactly are we making all this electricity in the first place? Are we critically dependent on fossil fuels to maintain anything like our present lifestyles - for better or worse? I’m not in the middle of these arguments. Instead I’m somewhere way off to the side. I gravitate toward quiet pragmatic work-arounds while everyone else bickers. So I’ll offer my take on the subject for whatever its worth.

Induction cooktops are all the rage with a certain segment of society. The argument goes something like this. Unlike gas stoves, they don’t generate toxic fumes which are associated with asthma and other ailments. Induction is incredibly efficient because it uses a small amount of energy to heat ferrous pots and pans directly via magnets. The cooktop remains cool even while in use. Only the pans and food get hot. Unlike older slow resistance coil electric stoves, induction heats up instantly. And the glass surface is smooth and easy to clean. What’s not to love?

I have friends who are ecologically minded. They do all the things. I love them for their pragmatic skills and cautious planning for an uncertain future. We bond over gardening, composting, home food preservation, carpentry projects, rainwater capture, emergency preparedness, and all sorts of community engagement efforts. They’re great people and very good cooks. Everything from Polish to Moroccan dishes are always excellent at their house.

As they slowly renovated their century old home, almost entirely by themselves, they had limitations and choices about how to proceed. One of them concerned the stove. The old stove was gas so there was no existing 220 volt electrical service for a new induction model. They had an electrician walk them through what was required to upgrade the system. First, they needed a new larger power outlet. New conduit would have to be run down to the breaker box in the garage. The breaker box would need to be upgraded to provide sufficient capacity. Then the line that brought in power from the street had to be boosted which involved jacking up the sidewalk. On top of all this, they would be obliged to pay the local utility company to upgrade the outside infrastructure that served the house.

All in, this was going to cost $21,000 - not including the price of the stove itself. Not surprisingly, they opted to replace the old gas stove with a really nice new gas stove imported from France. Even though the stove was a bit of an extravagance, it was still infinitely cheaper than the infrastructure required for an electric model. It was a rational decision. And they love the new stove.

Here’s where I step in with the oddball response. What if you inherit a gas stove and changing it just isn’t practical? Here’s a little kitchen gadget I’ve been toying with for a while. A sous vide is a small immersion heater that takes a pot or bucket of tap water from room temperature (usually about 55F / 13C) to the desired safe internal temperature of whatever food you’re cooking. For example, beef should be 145F / 63C. Chicken should be 165F / 74C. As far as I know there’s no “unsafe” temperature for vegetables. So this device slowly adds about 100F / 38C to whatever is being cooked and keeps it at that steady temperature. Compare that to a 3,560F / 1960C blast of heat coming from a gas burner.

I used a Kill A Watt meter to see how much electricity the sous vide used from start to finish. It pulled just about 1,000 watts in the beginning. Once the water hit the required temperature, energy consumption dropped down to almost nothing. It kicked up on occasion to maintain the correct cooking range, but overall it was minimal. For $129 this thing ticks a lot of boxes on the health and efficiency list. My duck breasts were delicious and it was impossible to burn them.

A sous vide doesn’t do everything. It won’t brown your meat or caramelize your onions. That requires high heat and a bit of oil or butter. I’m not convinced a stir fry would work with a sous vide either, and I wouldn’t cook pasta this way. These beef steaks, for example, were cooked to the exact right temperature, but they were a bit pale without searing. At the last minute I put them in a hot pan on the regular stove with some garlic for just a flash and got them browned. Perfect.

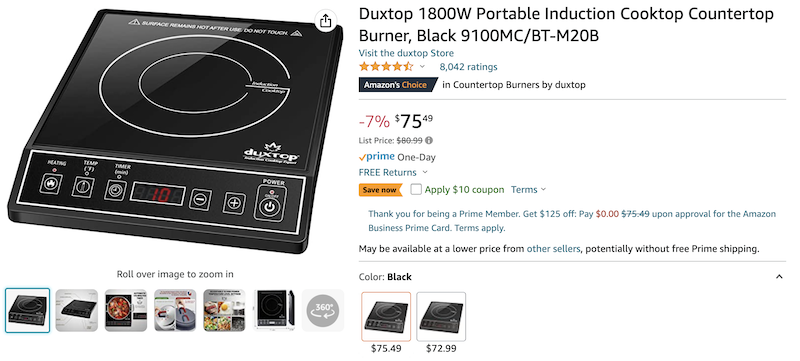

Here’s how this could be handled instead of the whole digging up the sidewalk and upgrading the utility service thing. You can buy a single portable induction cooktop that plugs into a normal wall outlet for $75. I actually bought one of these for a friend as a housewarming gift when he moved into a new studio apartment that didn’t have much of a kitchen. He loves it. For $133 you could buy a double unit. Now you can sauté all you want with no gas fumes and maximum efficiency. Need four burners? Six? Buy a few more of these portable units. Keep a few extra in a cabinet for those larger meals.

An Instant Pot is one of many similar products that can either slow cook or speed cook your food. I’ve made beef stew, tagine, chicken and matzo ball soup, lentil soup, split peas, and any number of other dishes with this ≈$100 machine. Coincidentally, it has settings that allow it to function as a sous vide and it can be pressed into service as a de facto frying pan in a pinch. I’ve even heard some types of cakes can be made in them, although I remain skeptical. There’s nothing magical about these products. They’re plain old electric resistance elements with a little computer chip to regulate them. The body of the device is thick and well insulated and has a tight fitting lid to preserve whatever energy is used to create heat.

Here’s another twist on low power kitchen appliances. You can run them on a few off grid solar panels and a portable inverter battery. I’ve done exactly that several times as part of my emergency dry runs for power cuts. The panels are affordable and easy to DIY. I’m the least technical person I know and I installed this backup system in an afternoon by watching YouTube videos. This isn’t about “saving the planet.” It’s about having some version of civility when larger systems wobble. I can make some of my own electricity at home, but I can’t make my own gas.

My point here is there are ways ordinary people can switch to healthier non gas cooking at a reasonable price point without engaging in institutional drama or politics. I’m pretty sure my friends with the fancy French stove could cook equivalent meals with some simple plug and play equipment. Of course, stoves aren’t just about cooking. Our kitchens are statements about who we are and how we want to enjoy our homes. A lot of appliances are really about status. That’s fine. But let’s be clear about our goals and not pretend otherwise.

Here’s my advice to anyone who is contemplating a transition to an all electric kitchen. Skip the big complex projects. Combine a few of these small devices and leave the gas stove right where it is. You can fire it up on Thanksgiving or when you decide to make three trays of lasagna. For everything else, you really don’t need it. If you’re worried about gas fumes from pilot lights you can slide the stove away from the wall, reach back behind, and turn off the gas valve at the pipe. It takes five minutes and costs nothing. And you can clean under the stove while you’re at it. This ain’t rocket science folks.